Building an Application With OTP

We've now seen how to use generic servers, finite state machine, event handlers and supervisors. We've not exactly seen how to use them together to build applications and tools, though.

An Erlang application is a group of related code and processes. An OTP application specifically uses OTP behaviours for its processes, and then wraps them in a very specific structure that tells the VM how to set everything up and then tear it down.

So in this chapter, we're going to build an application with OTP components, but not a full OTP one because we won't do the whole wrapping up just now. The details of complete OTP applications are a bit complex and warrant their own chapter (the next one). This one's going to be about implementing a process pool. The idea behind such a process pool is to manage and limit resources running in a system in a generic manner.

A Pool of Processes

So yes, a pool allows to limit how many processes run at once. A pool can also queue up jobs when the running workers limit is hit. The jobs can then be ran as soon as resources are freed up or simply block by telling the user they can't do anything else. Despite real world pools doing nothing similar to actual process pools, there are reasons to want to use the latter. A few of them could include:

- Limiting a server to N concurrent connections at most;

- Limiting how many files can be opened by an application;

- Giving different priorities to different subsystems of a release by allowing more resources for some and less for others. Let's say allowing more processes for client requests than processes in charge of generating reports for management.

- Allowing an application under occasional heavy loads coming in bursts to remain more stable during its entire life by queuing the tasks.

Our process pool application will thus need to support a few functions:

- Starting and stopping the application

- Starting and stopping a particular process pool (all the pools sit within the process pool application)

- Running a task in the pool and telling you it can't be started if the pool is full

- Running a task in the pool if there's room, otherwise keep the calling process waiting while the task is in the queue. Free the caller once the task can be run.

- Running a task asynchronously in the pool, as soon as possible. If no place is available, queue it up and run it whenever.

These needs will help drive our program design. Also keep in mind that we can now use supervisors. And of course we want to use them. The thing is, if they give us new powers in term of robustness, they also impose a certain limit on flexibility. Let's explore that.

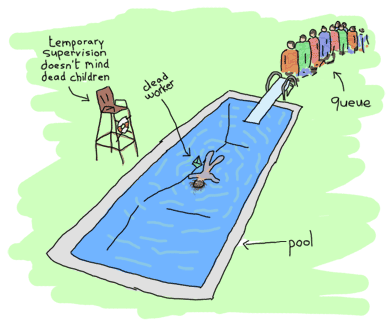

The Onion Layer Theory

To help ourselves design an application with supervisors, it helps to have an idea of what needs supervision and how it needs to be supervised. You'll recall we have different strategies with different settings; these will fit for different kinds of code with different kinds of errors. A rainbow of mistakes can be made!

One thing newcomers and even experienced Erlang programmers have trouble dealing with is usually how to cope with the loss of state. Supervisors kill processes, state is lost, woe is me. To help with this, we will identify different kinds of state:

- Static state. This type can easily be fetched from a config file, another process or the supervisor restarting the application.

- Dynamic state, composed of data you can re-compute. This includes state that you had to transform from its initial form to get where it is right now

- Dynamic data you can not recompute. This might include user input, live data, sequences of external events, etc.

Now, static data is somewhat easy to deal with. Most of the time you can get it straight from the supervisor. Same for the dynamic but re-computable data. In this case you might want to grab it and compute it within the init/1 function, or anywhere else in your code, really.

The most problematic kind of state is the dynamic data you can't recompute and that you can basically just hope not to lose. In some cases you'll be pushing that data to a database although that won't always be a good option.

The idea of an onion layered system is to allow all of these different states to be protected correctly by isolating different kinds of code from each other. It's process segregation.

The static state can be handled by supervisors, the system being started up, etc. Each time a child dies, the supervisor restarts them and can inject them with some form of static state, always being available. Because most supervisor definitions are rather static by nature, each layer of supervision you add acts as a shield protecting your application against their failure and the loss of their state.

The dynamic state that can be recomputed has a whole lot of available solutions: build it from the static data sent by the supervisors, go fetch it back from some other process, database, text file, the current environment or whatever. It should be relatively easy to get it back on each restart. The fact that you have supervisors that do a restarting job can be enough to help you keep that state alive.

The dynamic non-recomputable kind of state needs a more thoughtful approach. The real nature of an onion-layered approach takes shape here. The idea is that the most important data (or the hardest to find back) has to be the most protected type. The places where you are actually not allowed to fail is called the error kernel of your application.

The error kernel is likely the place where you'll want to use try ... catches more than anywhere else, where handling exceptional cases is vital. This is what you want to be error-free. Careful testing has to be done around there, especially in cases where there is no way to go back. You don't want to lose a customer's order halfway through processing it, do you? Some operations are going to be considered safer than others. Because of this, we want to keep vital data in the safest core possible, and keeping everything somewhat dangerous outside of it. In specific terms, this means that all kinds of operations related together should be part of the same supervision trees, and the unrelated ones should be kept in different trees. Within the same tree, operations that are failure-prone but not vital can be in a separate sub-tree. When possible, only restart the part of the tree that needs it. We'll see an example of this when designing our actual process pool's supervision tree.

A Pool's Tree

So how should we organise these process pools? There are two schools of thought here. One tells people to design bottom-up (write all individual components, put them together as required) and another one tells us to write things top-down (design as if all the parts were there, then build them). Both approaches are equally valid depending on the circumstances and your personal style. For the sake of making things understandable, we're going to do things top-down here.

So what should our tree look like? Well our requirements include: being able to start the pool application as a whole, having many pools and each pool having many workers that can be queued. This already suggests a few possible design constraints.

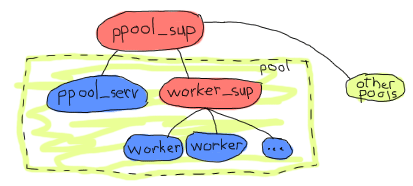

We will need one gen_server per pool. The server's job will be to maintain the counter of how many workers are in the pool. For convenience, the same server should also hold the queue of tasks. Who should be in charge of overlooking each of the workers, though? The server itself?

Doing it with the server is interesting. After all, it needs to track the processes to count them and supervising them itself is a nifty way to do it. Moreover neither the server nor the processes can crash without losing the state of all the others (otherwise the server can't track the tasks after it restarted). It has a few disadvantages too: the server has many responsibilities, can be seen as more fragile and duplicates the functionality of existing, better tested modules.

A good way to make sure all workers are properly accounted for would be to use a supervisor just for them

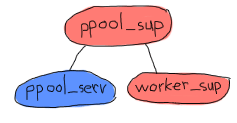

The one above, for example would have a single supervisor for all of the pools. Each pool is in fact a set of a pool server and a supervisor for workers. The pool server knows the existence of its worker supervisor and asks it to add items. Given adding children is a very dynamic thing with unknown limits so far, a simple_one_for_one supervisor shall be used.

Note: the name ppool is chosen because the Erlang standard library already has a pool module. Plus it's a terrible pool-related pun.

The advantage of doing things that way is that because the worker_sup supervisor will need to track only OTP workers of a single type, each pool is guaranteed to be about a well defined kind of worker, with simple management and restart strategies that are easy to define. This right here is one example of an error kernel being better defined. If I'm using a pool of sockets for web connections and another pool of servers in charge of log files, I am making sure that incorrect code or messy permissions in the log file section of my application won't be drowning out the processes in charge of the sockets. If the log files' pool crashes too much, they'll be shut down and their supervisor will stop. Oh wait!

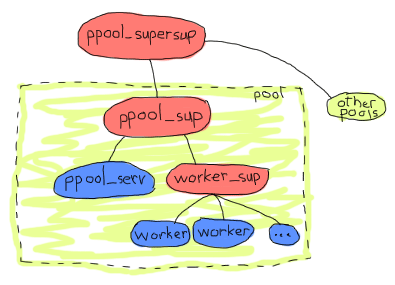

Right. Because all pools are under the same supervisor, a given pool or server restarting too many times in a short time span can take all the other pools down. This means what we might want to do is add one level of supervision. This will also make it much simpler to handle more than one pool at a time, so let's say the following will be our application architecture:

And that makes a bit more sense. From the onion layer perspective, all pools are independent, the workers are independent from each other and the ppool_serv server is going to be isolated from all the workers. That's good enough for the architecture, everything we need seems to be there. We can start working on the implementation, again, top to bottom.

Implementing the Supervisors

We can start with just the top level supervisor, ppool_supersup. All this one has to do is start the supervisor of a pool when required. We'll give it a few functions: start_link/0, which starts the whole application, stop/0, which stops it, start_pool/3, which creates a specific pool and stop_pool/1 which does the opposite. We also can't forget init/1, the only callback required by the supervisor behaviour:

-module(ppool_supersup).

-behaviour(supervisor).

-export([start_link/0, stop/0, start_pool/3, stop_pool/1]).

-export([init/1]).

start_link() ->

supervisor:start_link({local, ppool}, ?MODULE, []).

Here we gave the top level process pool supervisor the name ppool (this explains the use of {local, Name}, an OTP convention about registering gen_* processes on a node; another one exists for distributed registration). This is because we know we will only have one ppool per Erlang node and we can give it a name without worrying about clashes. Fortunately, the same name can then be used to stop the whole set of pools:

%% technically, a supervisor can not be killed in an easy way.

%% Let's do it brutally!

stop() ->

case whereis(ppool) of

P when is_pid(P) ->

exit(P, kill);

_ -> ok

end.

As the comments in the code explain it, we can not terminate a supervisor gracefully. The reason for this is that the OTP framework provides a well-defined shutdown procedure for all supervisors, but we can't use it from where we are right now. We'll see how to do it in the next chapter, but for now, brutally killing the supervisor is the best we can do.

What is the top level supervisor exactly? Well its only task is to hold pools in memory and supervise them. In this case, it will be a childless supervisor:

init([]) ->

MaxRestart = 6,

MaxTime = 3600,

{ok, {{one_for_one, MaxRestart, MaxTime}, []}}.

We can now focus on starting each individual pool's supervisor and attaching them to ppool. Given our initial requirements, we can determine that we'll need two parameters: the number of workers the pool will accept, and the {M,F,A} tuple that the worker supervisor will need to start each worker. We'll also add a name for good measure. We then pass this childspec to the process pool's supervisor as we start it:

start_pool(Name, Limit, MFA) ->

ChildSpec = {Name,

{ppool_sup, start_link, [Name, Limit, MFA]},

permanent, 10500, supervisor, [ppool_sup]},

supervisor:start_child(ppool, ChildSpec).

You can see each pool supervisor is asked to be permanent, has the arguments needed (notice how we're be changing programmer-submitted data into static data this way). The name of the pool is both passed to the supervisor and used as an identifier in the child specification. There's also a maximum shutdown time of 10500. There is no easy way to pick this value. Just make sure it's large enough that all the children will have time to stop. Play with them according to your needs and test and adapt yourself. You might as well try the infinity option if you just don't know.

To stop the pool, we need to ask the ppool super supervisor (the supersup!) to kill its matching child:

stop_pool(Name) ->

supervisor:terminate_child(ppool, Name),

supervisor:delete_child(ppool, Name).

This is possible because we gave the pool's Name as the childspec identifier. Great! We can now focus on each pool's direct supervisor!

Each ppool_sup will be in charge of the pool server and the worker supervisor.

Can you see the funny thing here? The ppool_serv process should be able to contact the worker_sup process. If we're to have them started by the same supervisor at the same time, we won't have any way to let ppool_serv know about worker_sup, unless we were to do some trickery with supervisor:which_children/1 (which would be sensitive to timing and somewhat risky), or giving a name to both the ppool_serv process (so that users can call it) and the supervisor. Now we don't want to give names to the supervisors because:

- The users don't need to call them directly

- We would need to dynamically generate atoms and that makes me nervous

- There is a better way.

The way to do it is basically to get the pool server to dynamically attach the worker supervisor to its ppool_sup. If this is vague, you'll get it soon. For now we only start the server:

-module(ppool_sup).

-export([start_link/3, init/1]).

-behaviour(supervisor).

start_link(Name, Limit, MFA) ->

supervisor:start_link(?MODULE, {Name, Limit, MFA}).

init({Name, Limit, MFA}) ->

MaxRestart = 1,

MaxTime = 3600,

{ok, {{one_for_all, MaxRestart, MaxTime},

[{serv,

{ppool_serv, start_link, [Name, Limit, self(), MFA]},

permanent,

5000, % Shutdown time

worker,

[ppool_serv]}]}}.

And that's about it. Note that the Name is passed to the server, along with self(), the supervisor's own pid. This will let the server call for the spawning of the worker supervisor; the MFA variable will be used in that call to let the simple_one_for_one supervisor know what kind of workers to run.

We'll get to how the server handles everything, but for now we'll finish writing all of the application's supervisors by writing ppool_worker_sup, in charge of all the workers:

-module(ppool_worker_sup).

-export([start_link/1, init/1]).

-behaviour(supervisor).

start_link(MFA = {_,_,_}) ->

supervisor:start_link(?MODULE, MFA).

init({M,F,A}) ->

MaxRestart = 5,

MaxTime = 3600,

{ok, {{simple_one_for_one, MaxRestart, MaxTime},

[{ppool_worker,

{M,F,A},

temporary, 5000, worker, [M]}]}}.

Simple stuff there. We picked a simple_one_for_one because workers could be added in very high number with a requirement for speed, plus we want to restrict their type. All the workers are temporary, and because we use an {M,F,A} tuple to start the worker, we can use any kind of OTP behaviour there.

The reason to make the workers temporary is twofold. First of all, we can not know for sure whether they need to be restarted or not in case of failure or what kind of restart strategy would be required for them. Secondly, the pool might only be useful if the worker's creator can have an access to the worker's pid, depending on the use case. For this to work in any safe and simple manner, we can't just restart workers as we please without tracking its creator and sending it a notification. This would make things quite complex just to grab a pid. Of course, you are free to write your own ppool_worker_sup that doesn't return pids but restarts them. There's nothing inherently wrong in that design.

Working on the Workers

The pool server is the most complex part of the application, where all the clever business logic happens. Here's a reminder of the operations we must support.

- Running a task in the pool and telling you it can't be started if the pool is full

- Running a task in the pool if there's place, otherwise keep the calling process waiting while the task is in the queue, until it can be run.

- Running a task asynchronously in the pool, as soon as possible. If no place is available, queue it up and run it whenever.

The first one will be done by a function named run/2, the second by sync_queue/2 and the last one by async_queue/2:

-module(ppool_serv).

-behaviour(gen_server).

-export([start/4, start_link/4, run/2, sync_queue/2, async_queue/2, stop/1]).

-export([init/1, handle_call/3, handle_cast/2, handle_info/2,

code_change/3, terminate/2]).

start(Name, Limit, Sup, MFA) when is_atom(Name), is_integer(Limit) ->

gen_server:start({local, Name}, ?MODULE, {Limit, MFA, Sup}, []).

start_link(Name, Limit, Sup, MFA) when is_atom(Name), is_integer(Limit) ->

gen_server:start_link({local, Name}, ?MODULE, {Limit, MFA, Sup}, []).

run(Name, Args) ->

gen_server:call(Name, {run, Args}).

sync_queue(Name, Args) ->

gen_server:call(Name, {sync, Args}, infinity).

async_queue(Name, Args) ->

gen_server:cast(Name, {async, Args}).

stop(Name) ->

gen_server:call(Name, stop).

For start/4 and start_link/4, Args are going to be the additional arguments passed to the A part of the {M,F,A} triple sent to the supervisor. Note that for the synchronous queue, I've set the waiting time to infinity.

As mentioned earlier, we have to start the supervisor from within the server. If you're adding the code as we go, you might want to include an empty gen_server template (or use the completed file) to follow along, because we'll do things on a per-feature basis rather than just reading the server from top to bottom.

The first thing we do is handle the creation of the supervisor. If you remember last chapter's bit on dynamic supervision, we do not need a simple_one_for_one for cases where we need few children added, so supervisor:start_child/2 ought to do it. We'll first define the child specification of the worker supervisor:

%% The friendly supervisor is started dynamically!

-define(SPEC(MFA),

{worker_sup,

{ppool_worker_sup, start_link, [MFA]},

temporary,

10000,

supervisor,

[ppool_worker_sup]}).

Nothing too special there. We can then define the inner state of the server. We know we will have to track a few pieces of data: the number of process that can be running, the pid of the supervisor and a queue for all the jobs. To know when a worker's done running and to fetch one from the queue to start it, we will need to track each worker from the server. The sane way to do this is with monitors, so we'll also add a refs field to our state record to keep all the monitor references in memory:

-record(state, {limit=0,

sup,

refs,

queue=queue:new()}).

With this ready, we can start implementing the init function. The natural thing to try is the following:

init({Limit, MFA, Sup}) ->

{ok, Pid} = supervisor:start_child(Sup, ?SPEC(MFA)),

link(Pid),

{ok, #state{limit=Limit, refs=gb_sets:empty()}}.

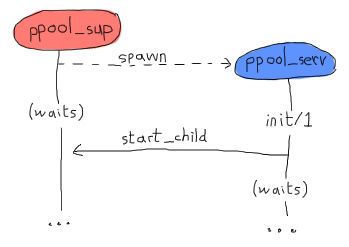

and get going. However, this code is wrong. The way things work with gen_* behaviours is that the process that spawns the behaviour waits until the init/1 function returns before resuming its processing. This means that by calling supervisor:start_child/2 in there, we create the following deadlock:

Both processes will keep waiting for each other until there is a crash. The cleanest way to get around this is to create a special message that the server will send to itself to be able to handle it in handle_info/2 as soon as it has returned (and the pool supervisor has become free):

init({Limit, MFA, Sup}) ->

%% We need to find the Pid of the worker supervisor from here,

%% but alas, this would be calling the supervisor while it waits for us!

self() ! {start_worker_supervisor, Sup, MFA},

{ok, #state{limit=Limit, refs=gb_sets:empty()}}.

This one is cleaner. We can then head out to the handle_info/2 function and add the following clauses:

handle_info({start_worker_supervisor, Sup, MFA}, S = #state{}) ->

{ok, Pid} = supervisor:start_child(Sup, ?SPEC(MFA)),

link(Pid),

{noreply, S#state{sup=Pid}};

handle_info(Msg, State) ->

io:format("Unknown msg: ~p~n", [Msg]),

{noreply, State}.

The first clause is the interesting one here. We find the message we sent ourselves (which will necessarily be the first one received), ask the pool supervisor to add the worker supervisor, track this Pid and voilà! Our tree is now fully initialized. Whew. You can try compiling everything to make sure no mistake has been made so far. Unfortunately we still can't test the application because too much stuff is missing.

Note: Don't worry if you do not like the idea of building the whole application before running it. Things are being done this way to show a cleaner reasoning of the whole thing. While I did have the general design in mind (the same one I illustrated earlier), I started writing this pool application in a little test-driven manner with a few tests here and there and a bunch of refactorings to get everything to a functional state.

Few Erlang programmers (much like programmers of most other languages) will be able to produce production-ready code on their first try, and the author is not as clever as the examples might make it look like.

Alright, so we've got this bit solved. Now we'll take care of the run/2 function. This one is a synchronous call with the message of the form {run, Args} and works as follows:

handle_call({run, Args}, _From, S = #state{limit=N, sup=Sup, refs=R}) when N > 0 ->

{ok, Pid} = supervisor:start_child(Sup, Args),

Ref = erlang:monitor(process, Pid),

{reply, {ok,Pid}, S#state{limit=N-1, refs=gb_sets:add(Ref,R)}};

handle_call({run, _Args}, _From, S=#state{limit=N}) when N =< 0 ->

{reply, noalloc, S};

A long function head, but we can see most of the management taking place there. Whenever there are places left in the pool (the original limit N being decided by the programmer adding the pool in the first place), we accept to start the worker. We then set up a monitor to know when it's done, store all of this in our state, decrement the counter and off we go.

In the case no space is available, we simply reply with noalloc.

The calls to sync_queue/2 will give a very similar implementation:

handle_call({sync, Args}, _From, S = #state{limit=N, sup=Sup, refs=R}) when N > 0 ->

{ok, Pid} = supervisor:start_child(Sup, Args),

Ref = erlang:monitor(process, Pid),

{reply, {ok,Pid}, S#state{limit=N-1, refs=gb_sets:add(Ref,R)}};

handle_call({sync, Args}, From, S = #state{queue=Q}) ->

{noreply, S#state{queue=queue:in({From, Args}, Q)}};

If there is space for more workers, then the first clause is going to do exactly the same as we did for run/2. The difference comes in the case where no workers can run. Rather than replying with noalloc as we did last time, this one doesn't reply to the caller, keeps the From information and enqueues it for a later time when there is space for the worker to be run. We'll see how we dequeue them and handle them soon enough, but for now, we'll finish the handle_call/3 callback with the following clauses:

handle_call(stop, _From, State) ->

{stop, normal, ok, State};

handle_call(_Msg, _From, State) ->

{noreply, State}.

Which handle the unknown cases and the stop/1 call. We can now focus on getting async_queue/2 working. Because async_queue/2 basically does not care when the worker is ran and expects absolutely no reply, it was decided to make it a cast rather than a call. You'll find the logic of it to be awfully similar to the two previous options:

handle_cast({async, Args}, S=#state{limit=N, sup=Sup, refs=R}) when N > 0 ->

{ok, Pid} = supervisor:start_child(Sup, Args),

Ref = erlang:monitor(process, Pid),

{noreply, S#state{limit=N-1, refs=gb_sets:add(Ref,R)}};

handle_cast({async, Args}, S=#state{limit=N, queue=Q}) when N =< 0 ->

{noreply, S#state{queue=queue:in(Args,Q)}};

%% Not going to explain this one!

handle_cast(_Msg, State) ->

{noreply, State}.

Again, the only big difference apart from not replying is that when there is no place left for a worker it is queued. This time though, we have no From information and just send it to the queue without it; the limit doesn't change in this case.

When do we know it's time to dequeue something? Well, we have monitors set all around the place and we're storing their references in a gb_sets. Whenever a worker goes down, we're notified of it. Let's work from there:

handle_info({'DOWN', Ref, process, _Pid, _}, S = #state{refs=Refs}) ->

io:format("received down msg~n"),

case gb_sets:is_element(Ref, Refs) of

true ->

handle_down_worker(Ref, S);

false -> %% Not our responsibility

{noreply, S}

end;

handle_info({start_worker_supervisor, Sup, MFA}, S = #state{}) ->

...

handle_info(Msg, State) ->

...

What we do in the snippet is make sure the 'DOWN' message we get comes from a worker. If it doesn't come from one (which would be surprising), we just ignore it. However, if the message really is what we want, we call a function named handle_down_worker/2:

handle_down_worker(Ref, S = #state{limit=L, sup=Sup, refs=Refs}) ->

case queue:out(S#state.queue) of

{{value, {From, Args}}, Q} ->

{ok, Pid} = supervisor:start_child(Sup, Args),

NewRef = erlang:monitor(process, Pid),

NewRefs = gb_sets:insert(NewRef, gb_sets:delete(Ref,Refs)),

gen_server:reply(From, {ok, Pid}),

{noreply, S#state{refs=NewRefs, queue=Q}};

{{value, Args}, Q} ->

{ok, Pid} = supervisor:start_child(Sup, Args),

NewRef = erlang:monitor(process, Pid),

NewRefs = gb_sets:insert(NewRef, gb_sets:delete(Ref,Refs)),

{noreply, S#state{refs=NewRefs, queue=Q}};

{empty, _} ->

{noreply, S#state{limit=L+1, refs=gb_sets:delete(Ref,Refs)}}

end.

Quite a complex one. Because our worker is dead, we can look in the queue for the next one to run. We do this by popping one element out of the queue, and looking what the result is. If there is at least one element in the queue, it will be of the form {{value, Item}, NewQueue}. If the queue is empty, it returns {empty, SameQueue}. Furthermore, we know that when we have the value {From, Args}, it means this came from sync_queue/2 and that it came from async_queue/2 otherwise.

Both cases where the queue has tasks in it will behave roughly the same: a new worker is attached to the worker supervisor, the reference of the old worker's monitor is removed and replaced with the new worker's monitor reference. The only different aspect is that in the case of the synchronous call, we send a manual reply while in the other we can remain silent. That's about it.

In the case the queue was empty, we need to do nothing but increment the worker limit by one.

The last thing to do is add the standard OTP callbacks:

code_change(_OldVsn, State, _Extra) ->

{ok, State}.

terminate(_Reason, _State) ->

ok.

That's it, our pool is ready to be used! It is a very unfriendly pool, though. All the functions we need to use are scattered around the place. Some are in ppool_supersup, some are in ppool_serv. Plus the module names are long for no reason. To make things nicer, add the following API module (just abstracting the calls away) to the application's directory:

%%% API module for the pool

-module(ppool).

-export([start_link/0, stop/0, start_pool/3,

run/2, sync_queue/2, async_queue/2, stop_pool/1]).

start_link() ->

ppool_supersup:start_link().

stop() ->

ppool_supersup:stop().

start_pool(Name, Limit, {M,F,A}) ->

ppool_supersup:start_pool(Name, Limit, {M,F,A}).

stop_pool(Name) ->

ppool_supersup:stop_pool(Name).

run(Name, Args) ->

ppool_serv:run(Name, Args).

async_queue(Name, Args) ->

ppool_serv:async_queue(Name, Args).

sync_queue(Name, Args) ->

ppool_serv:sync_queue(Name, Args).

And now we're done for real!

Note: you'll have noticed that our process pool doesn't limit the number of items that can be stored in the queue. In some cases, a real server application will need to put a ceiling on how many things can be queued to avoid crashing when too much memory is used, although the problem can be circumvented if you only use run/2 and sync_queue/2 with a fixed number of callers (if all content producers are stuck waiting for free space in the pool, they stop producing so much content in the first place).

Adding a limit to the queue size is left as an exercise to the reader, but fear not because it is relatively simple to do; you will need to pass a new parameter to all functions up to the server, which will then check the limit before any queuing.

Additionally, to control the load of your system, you sometimes want to impose limits closer to their source by using synchronous calls. Synchronous calls allow to block incoming queries when the system is getting swamped by producers faster than consumers; this generally helps keep it more responsive than a free-for-all load.

Writing a Worker

Look at me go, I'm lying all the time! The pool isn't really ready to be used. We don't have a worker at the moment. I forgot. This is a shame because we all know that in the chapter about writing a concurrent application, we've written ourselves a nice task reminder. It apparently wasn't enough for me, so for this one right here, I'll have us writing a nagger.

It will basically be a worker for each task, and the worker will keep nagging us by sending repeated messages until a given deadline. It'll be able to take:

- a time delay for which to nag,

- an address (pid) to say where the messages should be sent

- a nagging message to be sent in the process mailbox, including the nagger's own pid to be able to call...

- ... a stop function to say the task is done and that the nagger can stop nagging

Here we go:

%% demo module, a nagger for tasks,

%% because the previous one wasn't good enough

-module(ppool_nagger).

-behaviour(gen_server).

-export([start_link/4, stop/1]).

-export([init/1, handle_call/3, handle_cast/2,

handle_info/2, code_change/3, terminate/2]).

start_link(Task, Delay, Max, SendTo) ->

gen_server:start_link(?MODULE, {Task, Delay, Max, SendTo} , []).

stop(Pid) ->

gen_server:call(Pid, stop).

Yes, we're going to be using yet another gen_server. You'll find out that people use them all the time, even when sometimes not appropriate! It's important to remember that our pool can accept any OTP compliant process, not just gen_servers.

init({Task, Delay, Max, SendTo}) ->

{ok, {Task, Delay, Max, SendTo}, Delay}.

This just takes the basic data and forwards it. Again, Task is the thing to send as a message, Delay is the time spent in between each sending, Max is the number of times it's going to be sent and SendTo is a pid or a name where the message will go. Note that Delay is passed as a third element of the tuple, which means timeout will be sent to handle_info/2 after Delay milliseconds.

Given our API above, most of the server is rather straightforward:

%%% OTP Callbacks

handle_call(stop, _From, State) ->

{stop, normal, ok, State};

handle_call(_Msg, _From, State) ->

{noreply, State}.

handle_cast(_Msg, State) ->

{noreply, State}.

handle_info(timeout, {Task, Delay, Max, SendTo}) ->

SendTo ! {self(), Task},

if Max =:= infinity ->

{noreply, {Task, Delay, Max, SendTo}, Delay};

Max =< 1 ->

{stop, normal, {Task, Delay, 0, SendTo}};

Max > 1 ->

{noreply, {Task, Delay, Max-1, SendTo}, Delay}

end.

%% We cannot use handle_info below: if that ever happens,

%% we cancel the timeouts (Delay) and basically zombify

%% the entire process. It's better to crash in this case.

%% handle_info(_Msg, State) ->

%% {noreply, State}.

code_change(_OldVsn, State, _Extra) ->

{ok, State}.

terminate(_Reason, _State) -> ok.

The only somewhat complex part here lies in the handle_info/2 function. As seen back in the gen_server chapter, every time a timeout is hit (in this case, after Delay milliseconds), the timeout message is sent to the process. Based on this, we check how many nags were sent to know if we have to send more or just quit. With this worker done, we can actually try this process pool!

Run Pool Run

We can now play with the pool compile all the files and start the pool top-level supervisor itself:

$ erlc *.erl

$ erl

Erlang R14B02 (erts-5.8.3) [source] [64-bit] [smp:4:4] [rq:4] [async-threads:0] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false]

Eshell V5.8.3 (abort with ^G)

1> ppool:start_link().

{ok,<0.33.0>}

From this point, we can try a bunch of different features of the nagger as a pool:

2> ppool:start_pool(nagger, 2, {ppool_nagger, start_link, []}).

{ok,<0.35.0>}

3> ppool:run(nagger, ["finish the chapter!", 10000, 10, self()]).

{ok,<0.39.0>}

4> ppool:run(nagger, ["Watch a good movie", 10000, 10, self()]).

{ok,<0.41.0>}

5> flush().

Shell got {<0.39.0>,"finish the chapter!"}

Shell got {<0.39.0>,"finish the chapter!"}

ok

6> ppool:run(nagger, ["clean up a bit", 10000, 10, self()]).

noalloc

7> flush().

Shell got {<0.41.0>,"Watch a good movie"}

Shell got {<0.39.0>,"finish the chapter!"}

Shell got {<0.41.0>,"Watch a good movie"}

Shell got {<0.39.0>,"finish the chapter!"}

Shell got {<0.41.0>,"Watch a good movie"}

...

Everything seems to work rather well for the synchronous non-queued runs. The pool is started, tasks are added and messages are sent to the right destination. When we try to run more tasks than allowed, allocation is denied to us. No time for cleaning up, sorry! The others still run fine though.

Note: the ppool is started with start_link/0. If at any time you make an error in the shell, you take down the whole pool and have to start over again. This issue will be addressed in the next chapter.

Note: of course a cleaner nagger would probably call an event manager used to forward messages correctly to all appropriate media. In practice though, many products, protocols and libraries are prone to change and I always hated books that are no longer good to read once external dependencies have passed their time. As such, I tend to keep all external dependencies rather low, if not entirely absent from this tutorial.

We can try the queuing facilities (asynchronous), just to see:

8> ppool:async_queue(nagger, ["Pay the bills", 30000, 1, self()]).

ok

9> ppool:async_queue(nagger, ["Take a shower", 30000, 1, self()]).

ok

10> ppool:async_queue(nagger, ["Plant a tree", 30000, 1, self()]).

ok

<wait a bit>

received down msg

received down msg

11> flush().

Shell got {<0.70.0>,"Pay the bills"}

Shell got {<0.72.0>,"Take a shower"}

<wait some more>

received down msg

12> flush().

Shell got {<0.74.0>,"Plant a tree"}

ok

Great! So the queuing works. The log here doesn't show everything in a very clear manner, but what happens there is that the two first naggers run as soon as possible. Then, the worker limit is hit and we need to queue the third one (planting a tree). When the nags for paying the bills are done for, the tree nagger is scheduled and sends the message a bit later.

The synchronous one will behave differently:

13> ppool:sync_queue(nagger, ["Pet a dog", 20000, 1, self()]).

{ok,<0.108.0>}

14> ppool:sync_queue(nagger, ["Make some noise", 20000, 1, self()]).

{ok,<0.110.0>}

15> ppool:sync_queue(nagger, ["Chase a tornado", 20000, 1, self()]).

received down msg

{ok,<0.112.0>}

received down msg

16> flush().

Shell got {<0.108.0>,"Pet a dog"}

Shell got {<0.110.0>,"Make some noise"}

ok

received down msg

17> flush().

Shell got {<0.112.0>,"Chase a tornado"}

ok

Again, the log isn't as clear as if you tried it yourself (which I encourage). The basic sequence of events is that two workers are added to the pool. They aren't done running and when we try to add a third one, the shell gets locked up until ppool_serv (under the process name nagger) receives a worker's down message (received down msg). After this, our call to sync_queue/2 can return and give us the pid of our brand new worker.

We can now get rid of the pool as a whole:

18> ppool:stop_pool(nagger). ok 19> ppool:stop(). ** exception exit: killed

All pools will be terminated if you decide to just call ppool:stop(), but you'll receive a bunch of error messages. This is because we brutally kill the ppool_supersup process rather than taking it down correctly (which in turns crashes all child pools), but next chapter will cover how to do that cleanly.

Cleaning the Pool

Looking back on everything, we've managed to write a process pool to do some resource allocation in a somewhat simple manner. Everything can be handled in parallel, can be limited, and can be called from other processes. Pieces of your application that crash can, with the help of supervisors, be replaced transparently without breaking the entirety of it. Once the pool application was ready, we even rewrote a surprisingly large part of our reminder app with very little code.

Failure isolation for a single computer has been taken into account, concurrency is handled, and we now have enough architectural blocks to write some pretty solid server-side software, even though we still haven't really seen good ways to run them from the shell...

The next chapter will show how to package the ppool application into a real OTP application, ready to be shipped and use by other products. So far we haven't seen all the advanced features of OTP, but I can tell you that you're now on a level where you should be able to understand most intermediate to early advanced discussions on OTP and Erlang (the non-distributed part, at least). That's pretty good!