Syntax in functions

Pattern Matching

Now that we have the ability to store and compile our code, we can begin to write more advanced functions. Those that we have written so far were extremely simple and a bit underwhelming. We'll get to more interesting stuff. The first function we'll write will need to greet someone differently according to gender. In most languages you would need to write something similar to this:

function greet(Gender,Name)

if Gender == male then

print("Hello, Mr. %s!", Name)

else if Gender == female then

print("Hello, Mrs. %s!", Name)

else

print("Hello, %s!", Name)

end

With pattern-matching, Erlang saves you a whole lot of boilerplate code. A similar function in Erlang would look like this:

greet(male, Name) ->

io:format("Hello, Mr. ~s!", [Name]);

greet(female, Name) ->

io:format("Hello, Mrs. ~s!", [Name]);

greet(_, Name) ->

io:format("Hello, ~s!", [Name]).

I'll admit that the printing function is a lot uglier in Erlang than in many other languages, but that is not the point. The main difference here is that we used pattern matching to define both what parts of a function should be used and bind the values we need at the same time. There was no need to first bind the values and then compare them! So instead of:

function(Args)

if X then

Expression

else if Y then

Expression

else

Expression

We write:

function(X) -> Expression; function(Y) -> Expression; function(_) -> Expression.

in order to get similar results, but in a much more declarative style. Each of these function declarations is called a function clause. Function clauses must be separated by semicolons (;) and together form a function declaration. A function declaration counts as one larger statement, and it's why the final function clause ends with a period. It's a "funny" use of tokens to determine workflow, but you'll get used to it. At least you'd better hope so because there's no way out of it!

Note: io:format's formatting is done with the help of tokens being replaced in a string. The character used to denote a token is the tilde (~). Some tokens are built-in such as ~n, which will be changed to a line-break. Most other tokens denote a way to format data. The function call io:format("~s!~n",["Hello"]). includes the token ~s, which accepts strings and bitstrings as arguments, and ~n. The final output message would thus be "Hello!\n". Another widely used token is ~p, which will print an Erlang term in a nice way (adding in indentation and everything).

The io:format function will be seen in more details in later chapters dealing with input/output with more depth, but in the meantime you can try the following calls to see what they do: io:format("~s~n",[<<"Hello">>]), io:format("~p~n",[<<"Hello">>]), io:format("~~~n"), io:format("~f~n", [4.0]), io:format("~30f~n", [4.0]). They're a small part of all that's possible and all in all they look a bit like printf in many other languages. If you can't wait until the chapter about I/O, you can read the online documentation to know more.

Pattern matching in functions can get more complex and powerful than that. As you may or may not remember from a few chapters ago, we can pattern match on lists to get the heads and tails. Let's do this! Start a new module called functions in which we'll write a bunch of functions to explore many pattern matching avenues available to us:

-module(functions). -compile(export_all). %% replace with -export() later, for God's sake!

The first function we'll write is head/1, acting exactly like erlang:hd/1 which takes a list as an argument and returns its first element. It'll be done with the help of the cons operator (|):

head([H|_]) -> H.

If you type functions:head([1,2,3,4]). in the shell (once the module is compiled), you can expect the value '1' to be given back to you. Consequently, to get the second element of a list you would create the function:

second([_,X|_]) -> X.

The list will just be deconstructed by Erlang in order to be pattern matched. Try it in the shell!

1> c(functions).

{ok, functions}

2> functions:head([1,2,3,4]).

1

3> functions:second([1,2,3,4]).

2

This could be repeated for lists as long as you want, although it would be impractical to do it up to thousands of values. This can be fixed by writing recursive functions, which we'll see how to do later on. For now, let's concentrate on more pattern matching. The concept of free and bound variables we discussed in Starting Out (for real) still holds true for functions: we can then compare and know if two parameters passed to a function are the same or not. For this, we'll create a function same/2 that takes two arguments and tells if they're identical:

same(X,X) ->

true;

same(_,_) ->

false.

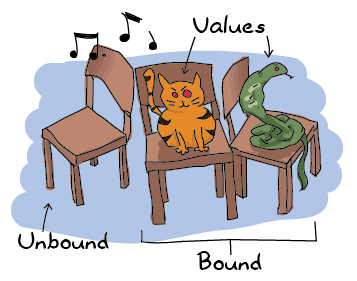

And it's that simple. Before explaining how the function works, we'll go over the concept of bound and unbound variables again, just in case:

If this game of musical chairs was Erlang, you'd want to sit on the empty chair. Sitting on one already occupied wouldn't end well! Joking aside, unbound variables are variables without any values attached to them (like our empty chair). Binding a variable is simply attaching a value to an unbound variable. In the case of Erlang, when you want to assign a value to a variable that is already bound, an error occurs unless the new value is the same as the old one. Let's imagine our snake on the right: if another snake comes around, it won't really change much to the game. You'll just have more angry snakes. If a different animal comes to sit on the chair (a honey badger, for example), things will go bad. Same values for a bound variable are fine, different ones are a bad idea. You can go back to the subchapter about Invariable Variables if this concept is not clear to you.

Back to our code: what happens when you call same(a,a) is that the first X is seen as unbound: it automatically takes the value a. Then when Erlang goes over to the second argument, it sees X is already bound. It then compares it to the a passed as the second argument and looks to see if it matches. The pattern matching succeeds and the function returns true. If the two values aren't the same, this will fail and go to the second function clause, which doesn't care about its arguments (when you're the last to choose, you can't be picky!) and will instead return false. Note that this function can effectively take any kind of argument whatsoever! It works for any type of data, not just lists or single variables. As a rather advanced example, the following function prints a date, but only if it is formatted correctly:

valid_time({Date = {Y,M,D}, Time = {H,Min,S}}) ->

io:format("The Date tuple (~p) says today is: ~p/~p/~p,~n",[Date,Y,M,D]),

io:format("The time tuple (~p) indicates: ~p:~p:~p.~n", [Time,H,Min,S]);

valid_time(_) ->

io:format("Stop feeding me wrong data!~n").

Note that it is possible to use the = operator in the function head, allowing us to match both the content inside a tuple ({Y,M,D}) and the tuple as a whole (Date). The function can be tested the following way:

4> c(functions).

{ok, functions}

5> functions:valid_time({{2011,09,06},{09,04,43}}).

The Date tuple ({2011,9,6}) says today is: 2011/9/6,

The time tuple ({9,4,43}) indicates: 9:4:43.

ok

6> functions:valid_time({{2011,09,06},{09,04}}).

Stop feeding me wrong data!

ok

There is a problem though! This function could take anything for values, even text or atoms, as long as the tuples are of the form {{A,B,C}, {D,E,F}}. This denotes one of the limits of pattern matching: it can either specify really precise values such as a known number of atom, or abstract values such as the head|tail of a list, a tuple of N elements, or anything (_ and unbound variables), etc. To solve this problem, we use guards.

Guards, Guards!

Guards are additional clauses that can go in a function's head to make pattern matching more expressive. As mentioned above, pattern matching is somewhat limited as it cannot express things like a range of value or certain types of data. A concept we couldn't represent is counting: is this 12 years old basketball player too short to play with the pros? Is this distance too long to walk on your hands? Are you too old or too young to drive a car? You couldn't answer these with simple pattern matching. I mean, you could represent the driving question such as:

old_enough(0) -> false; old_enough(1) -> false; old_enough(2) -> false; ... old_enough(14) -> false; old_enough(15) -> false; old_enough(_) -> true.

But it would be incredibly impractical. You can do it if you want, but you'll be alone to work on your code forever. If you want to eventually make friends, start a new guards module so we can type in the "correct" solution to the driving question:

old_enough(X) when X >= 16 -> true; old_enough(_) -> false.

And you're done! As you can see, this is much shorter and cleaner. Note that a basic rule for guard expression is they must return true to succeed. The guard will fail if it returns false or if it throws an exception. Suppose we now forbid people who are over 104 years old to drive. Our valid ages for drivers is now from 16 years old up to 104 years old. We need to take care of that, but how? Let's just add a second guard clause:

right_age(X) when X >= 16, X =< 104 ->

true;

right_age(_) ->

false.

The comma (,) acts in a similar manner to the operator andalso and the semicolon (;) acts a bit like orelse (described in "Starting Out (for real)"). Both guard expressions need to succeed for the whole guard to pass. We could also represent the function the opposite way:

wrong_age(X) when X < 16; X > 104 ->

true;

wrong_age(_) ->

false.

And we get correct results from that too. Test it if you want (you should always test stuff!). In guard expressions, the semi-colon (;) acts like the orelse operator: if the first guard fails, it then tries the second, and then the next one, until either one guard succeeds or they all fail.

You can use a few more functions than comparisons and boolean evaluation in functions, including math operations (A*B/C >= 0) and functions about data types, such as is_integer/1, is_atom/1, etc. (We'll get back on them in the following chapter). One negative point about guards is that they will not accept user-defined functions because of side effects. Erlang is not a purely functional programming language (like Haskell is) because it relies on side effects a lot: you can do I/O, send messages between actors or throw errors as you want and when you want. There is no trivial way to determine if a function you would use in a guard would or wouldn't print text or catch important errors every time it is tested over many function clauses. So instead, Erlang just doesn't trust you (and it may be right to do so!)

That being said, you should be good enough to understand the basic syntax of guards to understand them when you encounter them.

Note: I've compared , and ; in guards to the operators andalso and orelse. They're not exactly the same, though. The former pair will catch exceptions as they happen while the latter won't. What this means is that if there is an error thrown in the first part of the guard X >= N; N >= 0, the second part can still be evaluated and the guard might succeed; if an error was thrown in the first part of X >= N orelse N >= 0, the second part will also be skipped and the whole guard will fail.

However (there is always a 'however'), only andalso and orelse can be nested inside guards. This means (A orelse B) andalso C is a valid guard, while (A; B), C is not. Given their different use, the best strategy is often to mix them as necessary.

What the If!?

Ifs act like guards and share guards' syntax, but outside of a function clause's head. In fact, the if clauses are called Guard Patterns. Erlang's ifs are different from the ifs you'll ever encounter in most other languages; compared to them they're weird creatures that might have been more accepted had they had a different name. When entering Erlang's country, you should leave all you know about ifs at the door. Take a seat because we're going for a ride.

To see how similar to guards the if expression is, look at the following examples:

-module(what_the_if).

-export([heh_fine/0]).

heh_fine() ->

if 1 =:= 1 ->

works

end,

if 1 =:= 2; 1 =:= 1 ->

works

end,

if 1 =:= 2, 1 =:= 1 ->

fails

end.

Save this as what_the_if.erl and let's try it:

1> c(what_the_if).

./what_the_if.erl:12: Warning: no clause will ever match

./what_the_if.erl:12: Warning: the guard for this clause evaluates to 'false'

{ok,what_the_if}

2> what_the_if:heh_fine().

** exception error: no true branch found when evaluating an if expression

in function what_the_if:heh_fine/0

Uh oh! the compiler is warning us that no clause from the if on line 12 (1 =:= 2, 1 =:= 1) will ever match because its only guard evaluates to false. Remember, in Erlang, everything has to return something, and if expressions are no exception to the rule. As such, when Erlang can't find a way to have a guard succeed, it will crash: it cannot not return something. As such, we need to add a catch-all branch that will always succeed no matter what. In most languages, this would be called an 'else'. In Erlang, we use 'true' (this explains why the VM has thrown "no true branch found" when it got mad):

oh_god(N) ->

if N =:= 2 -> might_succeed;

true -> always_does %% this is Erlang's if's 'else!'

end.

And now if we test this new function (the old one will keep spitting warnings, ignore them or take them as a reminder of what not to do):

3> c(what_the_if).

./what_the_if.erl:12: Warning: no clause will ever match

./what_the_if.erl:12: Warning: the guard for this clause evaluates to 'false'

{ok,what_the_if}

4> what_the_if:oh_god(2).

might_succeed

5> what_the_if:oh_god(3).

always_does

Here's another function showing how to use many guards in an if expression. The function also illustrates how any expression must return something: Talk has the result of the if expression bound to it, and is then concatenated in a string, inside a tuple. When reading the code, it's easy to see how the lack of a true branch would mess things up, considering Erlang has no such thing as a null value (ie.: Lisp's NIL, C's NULL, Python's None, etc):

%% note, this one would be better as a pattern match in function heads!

%% I'm doing it this way for the sake of the example.

help_me(Animal) ->

Talk = if Animal == cat -> "meow";

Animal == beef -> "mooo";

Animal == dog -> "bark";

Animal == tree -> "bark";

true -> "fgdadfgna"

end,

{Animal, "says " ++ Talk ++ "!"}.

And now we try it:

6> c(what_the_if).

./what_the_if.erl:12: Warning: no clause will ever match

./what_the_if.erl:12: Warning: the guard for this clause evaluates to 'false'

{ok,what_the_if}

7> what_the_if:help_me(dog).

{dog,"says bark!"}

8> what_the_if:help_me("it hurts!").

{"it hurts!","says fgdadfgna!"}

You might be one of the many Erlang programmers wondering why 'true' was taken over 'else' as an atom to control flow; after all, it's much more familiar. Richard O'Keefe gave the following answer on the Erlang mailing lists. I'm quoting it directly because I couldn't have put it better:

It may be more FAMILIAR, but that doesn't mean 'else' is a good thing. I know that writing '; true ->' is a very easy way to get 'else' in Erlang, but we have a couple of decades of psychology-of-programming results to show that it's a bad idea. I have started to replace:

by if X > Y -> a() if X > Y -> a() ; true -> b() ; X =< Y -> b() end end if X > Y -> a() if X > Y -> a() ; X < Y -> b() ; X < Y -> b() ; true -> c() ; X ==Y -> c() end endwhich I find mildly annoying when _writing_ the code but enormously helpful when _reading_ it.

'Else' or 'true' branches should be "avoided" altogether: ifs are usually easier to read when you cover all logical ends rather than relying on a "catch all" clause.

As mentioned before, there are only a limited set of functions that can be used in guard expressions (we'll see more of them in Types (or lack thereof)). This is where the real conditional powers of Erlang must be conjured. I present to you: the case expression!

Note: All this horror expressed by the function names in what_the_if.erl is expressed in regards to the if language construct when seen from the perspective of any other languages' if. In Erlang's context, it turns out to be a perfectly logical construct with a confusing name.

In Case ... of

If the if expression is like a guard, a case ... of expression is like the whole function head: you can have the complex pattern matching you can use with each argument, and you can have guards on top of it!

As you're probably getting pretty familiar with the syntax, we won't need too many examples. For this one, we'll write the append function for sets (a collection of unique values) that we will represent as an unordered list. This is possibly the worst implementation possible in terms of efficiency, but what we want here is the syntax:

insert(X,[]) ->

[X];

insert(X,Set) ->

case lists:member(X,Set) of

true -> Set;

false -> [X|Set]

end.

If we send in an empty set (list) and a term X to be added, it returns us a list containing only X. Otherwise, the function lists:member/2 checks whether an element is part of a list and returns true if it is, false if it is not. In the case we already had the element X in the set, we do not need to modify the list. Otherwise, we add X as the list's first element.

In this case, the pattern matching was really simple. It can get more complex (you can compare your code with mine):

beach(Temperature) ->

case Temperature of

{celsius, N} when N >= 20, N =< 45 ->

'favorable';

{kelvin, N} when N >= 293, N =< 318 ->

'scientifically favorable';

{fahrenheit, N} when N >= 68, N =< 113 ->

'favorable in the US';

_ ->

'avoid beach'

end.

Here, the answer of "is it the right time to go to the beach" is given in 3 different temperature systems: Celsius, Kelvins and Fahrenheit degrees. Pattern matching and guards are combined in order to return an answer satisfying all uses. As pointed out earlier, case ... of expressions are pretty much the same thing as a bunch of function heads with guards. In fact we could have written our code the following way:

beachf({celsius, N}) when N >= 20, N =< 45 ->

'favorable';

...

beachf(_) ->

'avoid beach'.

This raises the question: when should we use if, case ... of or functions to do conditional expressions?

Which to use?

Which to use is rather hard to answer. The difference between function calls and case ... of are very minimal: in fact, they are represented the same way at a lower level, and using one or the other effectively has the same cost in terms of performance. One difference between both is when more than one argument needs to be evaluated: function(A,B) -> ... end. can have guards and values to match against A and B, but a case expression would need to be formulated a bit like:

case {A,B} of

Pattern Guards -> ...

end.

This form is rarely seen and might surprise the reader a bit. In similar situations, using a function call might be more appropriate. On the other hand the insert/2 function we had written earlier is arguably cleaner the way it is rather than having an immediate function call to track down on a simple true or false clause.

Then the other question is why would you ever use if, given cases and functions are flexible enough to even encompass if through guards? The rationale behind if is quite simple: it was added to the language as a short way to have guards without needing to write the whole pattern matching part when it wasn't needed.

Of course, all of this is more about personal preferences and what you may encounter more often. There is no good solid answer. The whole topic is still debated by the Erlang community from time to time. Nobody's going to go try to beat you up because of what you've chosen, as long as it is easy to understand. As Ward Cunningham once put it, "Clean code is when you look at a routine and it's pretty much what you expected."