Functionally Solving Problems

Sounds like we're ready to do something practical with all that Erlang juice we drank. Nothing new is going to be shown but how to apply bits of what we've seen before. The problems in this chapter were taken from Miran's Learn You a Haskell. I decided to take the same solutions so curious readers can compare solutions in Erlang and Haskell as they wish. If you do so, you might find the final results to be pretty similar for two languages with such different syntaxes. This is because once you know functional concepts, they're relatively easy to carry over to other functional languages.

Reverse Polish Notation Calculator

Most people have learned to write arithmetic expressions with the operators in-between the numbers ((2 + 2) / 5). This is how most calculators let you insert mathematical expressions and probably the notation you were taught to count with in school. This notation has the downside of needing you to know about operator precedence: multiplication and division are more important (have a higher precedence) than addition and subtraction.

Another notation exists, called prefix notation or Polish notation, where the operator comes before the operands. Under this notation, (2 + 2) / 5 would become (/ (+ 2 2) 5). If we decide to say + and / always take two arguments, then (/ (+ 2 2) 5) can simply be written as / + 2 2 5.

However, we will instead focus on Reverse Polish notation (or just RPN), which is the opposite of prefix notation: the operator follows the operands. The same example as above in RPN would be written 2 2 + 5 /. Other example expressions could be 9 * 5 + 7 or 10 * 2 * (3 + 4) / 2 which get translated to 9 5 * 7 + and 10 2 * 3 4 + * 2 /, respectively. This notation was used a whole lot in early models of calculators as it would take little memory to use. In fact some people still carry RPN calculators around. We'll write one of these.

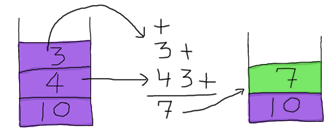

First of all, it might be good to understand how to read RPN expressions. One way to do it is to find the operators one by one and then regroup them with their operands by arity:

10 4 3 + 2 * - 10 (4 3 +) 2 * - 10 ((4 3 +) 2 *) - (10 ((4 3 +) 2 *) -) (10 (7 2 *) -) (10 14 -) -4

However, in the context of a computer or a calculator, a simpler way to do it is to make a stack of all the operands as we see them. Taking the mathematical expression 10 4 3 + 2 * -, the first operand we see is 10. We add that to the stack. Then there's 4, so we also push that on top of the stack. In third place, we have 3; let's push that one on the stack too. Our stack should now look like this:

![A stack showing the values [3 4 10]](https://learnyousomeerlang.com/static/img/stack1.png)

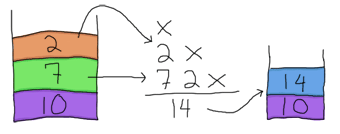

The next character to parse is a +. That one is a function of arity 2. In order to use it we will need to feed it two operands, which will be taken from the stack:

So we take that 7 and push it back on top of the stack (yuck, we don't want to keep these filthy numbers floating around!) The stack is now [7,10] and what's left of the expression is 2 * -. We can take the 2 and push it on top of the stack. We then see *, which needs two operands to work. Again, we take them from the stack:

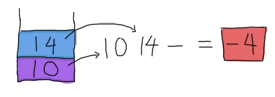

And push 14 back on top of our stack. All that remains is -, which also needs two operands. O Glorious luck! There are two operands left in our stack. Use them!

And so we have our result. This stack-based approach is relatively fool-proof and the low amount of parsing needed to be done before starting to calculate results explains why it was a good idea for old calculators to use this. There are other reasons to use RPN, but this is a bit out of the scope of this guide, so you might want to hit the Wikipedia article instead.

Writing this solution in Erlang is not too hard once we've done the complex stuff. It turns out the tough part is figuring out what steps need to be done in order to get our end result and we just did that. Neat. Open a file named calc.erl.

The first part to worry about is how we're going to represent a mathematical expression. To make things simple, we'll probably input them as a string: "10 4 3 + 2 * -". This string has whitespace, which isn't part of our problem-solving process, but is necessary in order to use a simple tokenizer. What would be usable then is a list of terms of the form ["10","4","3","+","2","*","-"] after going through the tokenizer. Turns out the function string:tokens/2 does just that:

1> string:tokens("10 4 3 + 2 * -", " ").

["10","4","3","+","2","*","-"]

That will be a good representation for our expression. The next part to define is the stack. How are we going to do that? You might have noticed that Erlang's lists act a lot like a stack. Using the cons (|) operator in [Head|Tail] effectively behaves the same as pushing Head on top of a stack (Tail, in this case). Using a list for a stack will be good enough.

To read the expression, we just have to do the same as we did when solving the problem by hand. Read each value from the expression, if it's a number, put it on the stack. If it's a function, pop all the values it needs from the stack, then push the result back in. To generalize, all we need to do is go over the whole expression as a loop only once and accumulate the results. Sounds like the perfect job for a fold!

What we need to plan for is the function that lists:foldl/3 will apply on every operator and operand of the expression. This function, because it will be run in a fold, will need to take two arguments: the first one will be the element of the expression to work with and the second one will be the stack.

We can start writing our code in the calc.erl file. We'll write the function responsible for all the looping and also the removal of spaces in the expression:

-module(calc).

-export([rpn/1]).

rpn(L) when is_list(L) ->

[Res] = lists:foldl(fun rpn/2, [], string:tokens(L, " ")),

Res.

We'll implement rpn/2 next. Note that because each operator and operand from the expression ends up being put on top of the stack, the solved expression's result will be on that stack. We need to get that last value out of there before returning it to the user. This is why we pattern match over [Res] and only return Res.

Alright, now to the harder part. Our rpn/2 function will need to handle the stack for all values passed to it. The head of the function will probably look like rpn(Op,Stack) and its return value like [NewVal|Stack]. When we get regular numbers, the operation will be:

rpn(X, Stack) -> [read(X)|Stack].

Here, read/1 is a function that converts a string to an integer or floating point value. Sadly, there is no built-in function to do this in Erlang (only one or the other). We'll add it ourselves:

read(N) ->

case string:to_float(N) of

{error,no_float} -> list_to_integer(N);

{F,_} -> F

end.

Where string:to_float/1 does the conversion from a string such as "13.37" to its numeric equivalent. However, if there is no way to read a floating point value, it returns {error,no_float}. When that happens, we need to call list_to_integer/1 instead.

Now back to rpn/2. The numbers we encounter all get added to the stack. However, because our pattern matches on anything (see Pattern Matching), operators will also get pushed on the stack. To avoid this, we'll put them all in preceding clauses. The first one we'll try this with is the addition:

rpn("+", [N1,N2|S]) -> [N2+N1|S];

rpn(X, Stack) -> [read(X)|Stack].

We can see that whenever we encounter the "+" string, we take two numbers from the top of the stack (N1,N2) and add them before pushing the result back onto that stack. This is exactly the same logic we applied when solving the problem by hand. Trying the program we can see that it works:

1> c(calc).

{ok,calc}

2> calc:rpn("3 5 +").

8

3> calc:rpn("7 3 + 5 +").

15

The rest is trivial, as you just need to add all the other operators:

rpn("+", [N1,N2|S]) -> [N2+N1|S];

rpn("-", [N1,N2|S]) -> [N2-N1|S];

rpn("*", [N1,N2|S]) -> [N2*N1|S];

rpn("/", [N1,N2|S]) -> [N2/N1|S];

rpn("^", [N1,N2|S]) -> [math:pow(N2,N1)|S];

rpn("ln", [N|S]) -> [math:log(N)|S];

rpn("log10", [N|S]) -> [math:log10(N)|S];

rpn(X, Stack) -> [read(X)|Stack].

Note that functions that take only one argument such as logarithms only need to pop one element from the stack. It is left as an exercise to the reader to add functions such as 'sum' or 'prod' which return the sum of all the elements read so far or the products of them all. To help you out, they are implemented in my version of calc.erl already.

To make sure this all works fine, we'll write very simple unit tests. Erlang's = operator can act as an assertion function. Assertions should crash whenever they encounter unexpected values, which is exactly what we need. Of course, there are more advanced testing frameworks for Erlang, including Common Test and EUnit. We'll check them out later, but for now the basic = will do the job:

rpn_test() ->

5 = rpn("2 3 +"),

87 = rpn("90 3 -"),

-4 = rpn("10 4 3 + 2 * -"),

-2.0 = rpn("10 4 3 + 2 * - 2 /"),

ok = try

rpn("90 34 12 33 55 66 + * - +")

catch

error:{badmatch,[_|_]} -> ok

end,

4037 = rpn("90 34 12 33 55 66 + * - + -"),

8.0 = rpn("2 3 ^"),

true = math:sqrt(2) == rpn("2 0.5 ^"),

true = math:log(2.7) == rpn("2.7 ln"),

true = math:log10(2.7) == rpn("2.7 log10"),

50 = rpn("10 10 10 20 sum"),

10.0 = rpn("10 10 10 20 sum 5 /"),

1000.0 = rpn("10 10 20 0.5 prod"),

ok.

The test function tries all operations; if there's no exception raised, the tests are considered successful. The first four tests check that the basic arithmetic functions work right. The fifth test specifies behaviour I have not explained yet. The try ... catch expects a badmatch error to be thrown because the expression can't work:

90 34 12 33 55 66 + * - + 90 (34 (12 (33 (55 66 +) *) -) +)

At the end of rpn/1, the values -3947 and 90 are left on the stack because there is no operator to work on the 90 that hangs there. Two ways to handle this problem are possible: either ignore it and only take the value on top of the stack (which would be the last result calculated) or crash because the arithmetic is wrong. Given Erlang's policy is to let it crash, it's what was chosen here. The part that actually crashes is the [Res] in rpn/1. That one makes sure only one element, the result, is left in the stack.

The few tests that are of the form true = FunctionCall1 == FunctionCall2 are there because you can't have a function call on the left hand side of =. It still works like an assert because we compare the comparison's result to true.

I've also added the test cases for the sum and prod operators so you can exercise yourselves implementing them. If all tests are successful, you should see the following:

1> c(calc).

{ok,calc}

2> calc:rpn_test().

ok

3> calc:rpn("1 2 ^ 2 2 ^ 3 2 ^ 4 2 ^ sum 2 -").

28.0

Where 28 is indeed equal to sum(1² + 2² + 3² + 4²) - 2. Try as many of them as you wish.

One thing that could be done to make our calculator better would be to make sure it raises badarith errors when it crashes because of unknown operators or values left on the stack, rather than our current badmatch error. It would certainly make debugging easier for the user of the calc module.

Heathrow to London

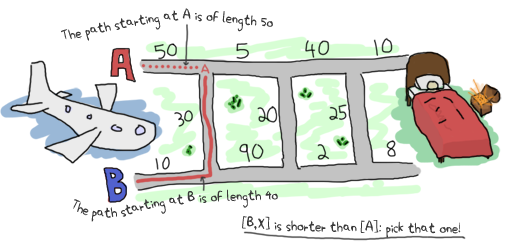

Our next problem is also taken from Learn You a Haskell. You're on a plane due to land at Heathrow airport in the next hours. You have to get to London as fast as possible; your rich uncle is dying and you want to be the first there to claim dibs on his estate.

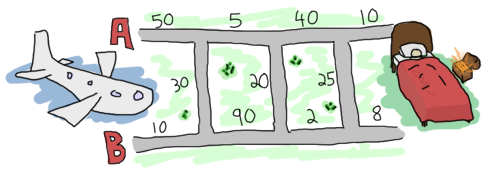

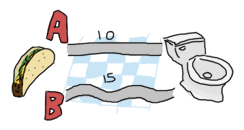

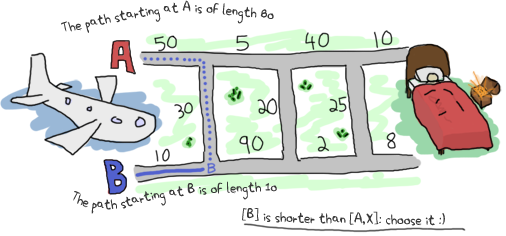

There are two roads going from Heathrow to London and a bunch of smaller streets linking them together. Because of speed limits and usual traffic, some parts of the roads and smaller streets take longer to drive on than others. Before you land, you decide to maximize your chances by finding the optimal path to his house. Here's the map you've found on your laptop:

Having become a huge fan of Erlang after reading online books, you decide to solve the problem using that language. To make it easier to work with the map, you enter data the following way in a file named road.txt:

50 10 30 5 90 20 40 2 25 10 8 0

The road is laid in the pattern: A1, B1, X1, A2, B2, X2, ..., An, Bn, Xn, where X is one of the roads joining the A side to the B side of the map. We insert a 0 as the last X segment, because no matter what we do we're at our destination already. Data can probably be organized in tuples of 3 elements (triples) of the form {A,B,X}.

The next thing you realize is that it's worth nothing to try to solve this problem in Erlang when you don't know how to solve it by hand to begin with. In order to do this, we'll use what recursion taught us.

When writing a recursive function, the first thing to do is to find our base case. For our problem at hand, this would be if we had only one tuple to analyze, that is, if we only had to choose between A, B (and crossing X, which in this case is useless because we're at destination):

Then the choice is only between picking which of path A or path B is the shortest. If you've learned your recursion right, you know that we ought to try and converge towards the base case. This means that on each step we'll take, we'll want to reduce the problem to choosing between A and B for the next step.

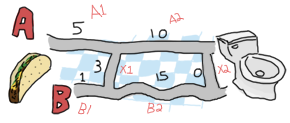

Let's extend our map and start over:

Ah! It gets interesting! How can we reduce the triple {5,1,3} to a strict choice between A and B? Let's see how many options are possible for A. To get to the intersection of A1 and A2 (I'll call this the point A1), I can either take road A1 directly (5), or come from B1 (1) and then cross over X1 (3). In this case, The first option (5) is longer than the second one (4). For the option A, the shortest path is [B, X]. So what are the options for B? You can either proceed from A1 (5) then cross over X1 (3), or strictly take the path B1 (1).

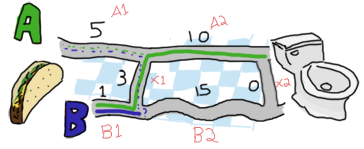

Alright! What we've got is a length 4 with the path [B, X] towards the first intersection A and a length 1 with the path [B] towards the intersection of B1 and B2. We then have to decide what to pick between going to the second point A (the intersection of A2 and the endpoint or X2) and the second point B (intersection of B2 and X2). To make a decision, I suggest we do the same as before. Now you don't have much choice but to obey, given I'm the guy writing this text. Here we go!

All possible paths to take in this case can be found in the same way as the previous one. We can get to the next point A by either taking the path A2 from [B, X], which gives us a length of 14 (14 = 4 + 10), or by taking B2 then X2 from [B], which gives us a length of 16 (16 = 1 + 15 + 0). In this case, the path [B, X, A] is better than [B, B, X].

We can also get to the next point B by either taking the path A2 from [B, X] and then crossing over X2 for a length of 14 (14 = 4 + 10 + 0), or by taking the road B2 from [B] for a length of 16 (16 = 1 + 15). Here, the best path is to pick the first option, [B, X, A, X].

So when this whole process is done, we're left with two paths, A or B, both of length 14. Either of them is the right one. The last selection will always have two paths of the same length, given the last X segment has a length 0. By solving our problem recursively, we've made sure to always get the shortest path at the end. Not too bad, eh?

Subtly enough, we've given ourselves the basic logical parts we need to build a recursive function. You can implement it if you want, but I promised we would have very few recursive functions to write ourselves. We'll use a fold.

Note: while I have shown folds being used and constructed with lists, folds represent a broader concept of iterating over a data structure with an accumulator. As such, folds can be implemented over trees, dictionaries, arrays, database tables, etc.

It is sometimes useful when experimenting to use abstractions like maps and folds; they make it easier to later change the data structure you use to work with your own logic.

So where were we? Ah, yes! We had the file we're going to feed as input ready. To do file manipulations, the file module is our best tool. It contains many functions common to many programming languages in order to deal with files themselves (setting permissions, moving files around, renaming and deleting them, etc.)

It also contains the usual functions to read and/or write from files such as: file:open/2 and file:close/1 to do as their names say (opening and closing files!), file:read/2 to get the content a file (either as string or a binary), file:read_line/1 to read a single line, file:position/3 to move the pointer of an open file to a given position, etc.

There's a bunch of shortcut functions in there too, such as file:read_file/1 (opens and reads the contents as a binary), file:consult/1 (opens and parses a file as Erlang terms) or file:pread/2 (changes a position and then reads) and pwrite/2 (changes the position and writes content).

With all these choices available, it's going to be easy to find a function to read our road.txt file. Because we know our road is relatively small, we're going to call file:read_file("road.txt").':

1> {ok, Binary} = file:read_file("road.txt").

{ok,<<"50\r\n10\r\n30\r\n5\r\n90\r\n20\r\n40\r\n2\r\n25\r\n10\r\n8\r\n0\r\n">>}

2> S = string:tokens(binary_to_list(Binary), "\r\n\t ").

["50","10","30","5","90","20","40","2","25","10","8","0"]

Note that in this case, I added a space (" ") and a tab ("\t") to the valid tokens so the file could have been written in the form "50 10 30 5 90 20 40 2 25 10 8 0" too. Given that list, we'll need to transform the strings into integers. We'll use a similar manner to what we used in our RPN calculator:

3> [list_to_integer(X) || X <- S]. [50,10,30,5,90,20,40,2,25,10,8,0]

Let's start a new module called road.erl and write this logic down:

-module(road).

-compile(export_all).

main() ->

File = "road.txt",

{ok, Bin} = file:read_file(File),

parse_map(Bin).

parse_map(Bin) when is_binary(Bin) ->

parse_map(binary_to_list(Bin));

parse_map(Str) when is_list(Str) ->

[list_to_integer(X) || X <- string:tokens(Str,"\r\n\t ")].

The function main/0 is here responsible for reading the content of the file and passing it on to parse_map/1. Because we use the function file:read_file/1 to get the contents out of road.txt, the result we obtain is a binary. For this reason, I've made the function parse_map/1 match on both lists and binaries. In the case of a binary, we just call the function again with the string being converted to a list (our function to split the string works on lists only.)

The next step in parsing the map would be to regroup the data into the {A,B,X} form described earlier. Sadly, there's no simple generic way to pull elements from a list 3 at a time, so we'll have to pattern match our way in a recursive function in order to do it:

group_vals([], Acc) ->

lists:reverse(Acc);

group_vals([A,B,X|Rest], Acc) ->

group_vals(Rest, [{A,B,X} | Acc]).

That function works in a standard tail-recursive manner; there's nothing too complex going on here. We'll just need to call it by modifying parse_map/1 a bit:

parse_map(Bin) when is_binary(Bin) ->

parse_map(binary_to_list(Bin));

parse_map(Str) when is_list(Str) ->

Values = [list_to_integer(X) || X <- string:tokens(Str,"\r\n\t ")],

group_vals(Values, []).

If we try and compile it all, we should now have a road that makes sense:

1> c(road).

{ok,road}

2> road:main().

[{50,10,30},{5,90,20},{40,2,25},{10,8,0}]

Ah yes, that looks right. We get the blocks we need to write our function that will then fit in a fold. For this to work, finding a good accumulator is necessary.

To decide what to use as an accumulator, the method I find the easiest to use is to imagine myself in the middle of the algorithm while it runs. For this specific problem, I'll imagine that I'm currently trying to find the shortest path of the second triple ({5,90,20}). To decide on which path is the best, I need to have the result from the previous triple. Luckily, we know how to do it, because we don't need an accumulator and we got all that logic out already. So for A:

And take the shortest of these two paths. For B, it was similar:

So now we know that the current best path coming from A is [B, X]. We also know it has a length of 40. For B, the path is simply [B] and the length is 10. We can use this information to find the next best paths for A and B by reapplying the same logic, but counting the previous ones in the expression. The other data we need is the path traveled so we can show it to the user. Given we need two paths (one for A and one for B) and two accumulated lengths, our accumulator can take the form {{DistanceA, PathA}, {DistanceB, PathB}}. That way, each iteration of the fold has access to all the state and we build it up to show it to the user in the end.

This gives us all the parameters our function will need: the {A,B,X} triples and an accumulator of the form {{DistanceA,PathA}, {DistanceB,PathB}}.

Putting this into code in order to get our accumulator can be done the following way:

shortest_step({A,B,X}, {{DistA,PathA}, {DistB,PathB}}) ->

OptA1 = {DistA + A, [{a,A}|PathA]},

OptA2 = {DistB + B + X, [{x,X}, {b,B}|PathB]},

OptB1 = {DistB + B, [{b,B}|PathB]},

OptB2 = {DistA + A + X, [{x,X}, {a,A}|PathA]},

{erlang:min(OptA1, OptA2), erlang:min(OptB1, OptB2)}.

Here, OptA1 gets the first option for A (going through A), OptA2 the second one (going through B then X). The variables OptB1 and OptB2 get the similar treatment for point B. Finally, we return the accumulator with the paths obtained.

About the paths saved in the code above, note that I decided to use the form [{x,X}] rather than [x] for the simple reason that it might be nice for the user to know the length of each segment. The other thing I'm doing is that I'm accumulating the paths backwards ({x,X} comes before {b,B}.) This is because we're in a fold, which is tail recursive: the whole list is reversed, so it is necessary to put the last one traversed before the others.

Finally, I use erlang:min/2 to find the shortest path. It might sound weird to use such a comparison function on tuples, but remember that every Erlang term can be compared to any other! Because the length is the first element of the tuple, we can sort them that way.

What's left to do is to stick that function into a fold:

optimal_path(Map) ->

{A,B} = lists:foldl(fun shortest_step/2, {{0,[]}, {0,[]}}, Map),

{_Dist,Path} = if hd(element(2,A)) =/= {x,0} -> A;

hd(element(2,B)) =/= {x,0} -> B

end,

lists:reverse(Path).

At the end of the fold, both paths should end up having the same distance, except one's going through the final {x,0} segment. The if looks at the last visited element of both paths and returns the one that doesn't go through {x,0}. Picking the path with the fewest steps (compare with length/1) would also work. Once the shortest one has been selected, it is reversed (it was built in a tail-recursive manner; you must reverse it). You can then display it to the world, or keep it secret and get your rich uncle's estate. To do that, you have to modify the main function to call optimal_path/1. Then it can be compiled.

main() ->

File = "road.txt",

{ok, Bin} = file:read_file(File),

optimal_path(parse_map(Bin)).

Oh, look! We've got the right answer! Great Job!

1> c(road).

{ok,road}

2> road:main().

[{b,10},{x,30},{a,5},{x,20},{b,2},{b,8}]

Or, to put it in a visual way:

![The shortest path, going through [b,x,a,x,b,b]](https://learnyousomeerlang.com/static/img/road1.4.png)

But you know what would be really useful? Being able to run our program from outside the Erlang shell. We'll need to change our main function again:

main([FileName]) ->

{ok, Bin} = file:read_file(FileName),

Map = parse_map(Bin),

io:format("~p~n",[optimal_path(Map)]),

erlang:halt().

The main function now has an arity of 1, needed to receive parameters from the command line. I've also added the function erlang:halt/0, which will shut down the Erlang VM after being called. I've also wrapped the call to optimal_path/1 into io:format/2 because that's the only way to have the text visible outside the Erlang shell.

With all of this, your road.erl file should now look like this (minus comments):

-module(road).

-compile(export_all).

main([FileName]) ->

{ok, Bin} = file:read_file(FileName),

Map = parse_map(Bin),

io:format("~p~n",[optimal_path(Map)]),

erlang:halt(0).

%% Transform a string into a readable map of triples

parse_map(Bin) when is_binary(Bin) ->

parse_map(binary_to_list(Bin));

parse_map(Str) when is_list(Str) ->

Values = [list_to_integer(X) || X <- string:tokens(Str,"\r\n\t ")],

group_vals(Values, []).

group_vals([], Acc) ->

lists:reverse(Acc);

group_vals([A,B,X|Rest], Acc) ->

group_vals(Rest, [{A,B,X} | Acc]).

%% Picks the best of all paths, woo!

optimal_path(Map) ->

{A,B} = lists:foldl(fun shortest_step/2, {{0,[]}, {0,[]}}, Map),

{_Dist,Path} = if hd(element(2,A)) =/= {x,0} -> A;

hd(element(2,B)) =/= {x,0} -> B

end,

lists:reverse(Path).

%% actual problem solving

%% change triples of the form {A,B,X}

%% where A,B,X are distances and a,b,x are possible paths

%% to the form {DistanceSum, PathList}.

shortest_step({A,B,X}, {{DistA,PathA}, {DistB,PathB}}) ->

OptA1 = {DistA + A, [{a,A}|PathA]},

OptA2 = {DistB + B + X, [{x,X}, {b,B}|PathB]},

OptB1 = {DistB + B, [{b,B}|PathB]},

OptB2 = {DistA + A + X, [{x,X}, {a,A}|PathA]},

{erlang:min(OptA1, OptA2), erlang:min(OptB1, OptB2)}.

And running the code:

$ erlc road.erl

$ erl -noshell -run road main road.txt

[{b,10},{x,30},{a,5},{x,20},{b,2},{b,8}]

And yep, it's right! It's pretty much all you need to do to get things to work. You could make yourself a bash/batch file to wrap the line into a single executable, or you could check out escript to get similar results.

As we've seen with these two exercises, solving problems is much easier when you break them off in small parts that you can solve individually before piecing everything together. It's also not worth much to go ahead and program something without understanding it. Finally, a few tests are always appreciated. They'll let you make sure everything works fine and will let you change the code without changing the results at the end.